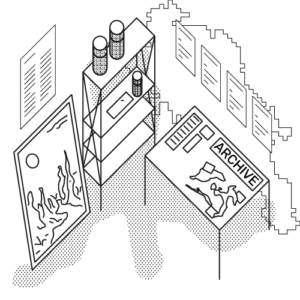

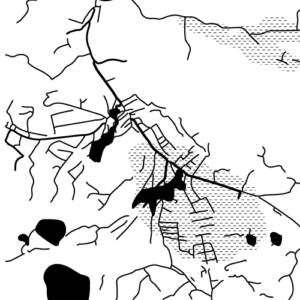

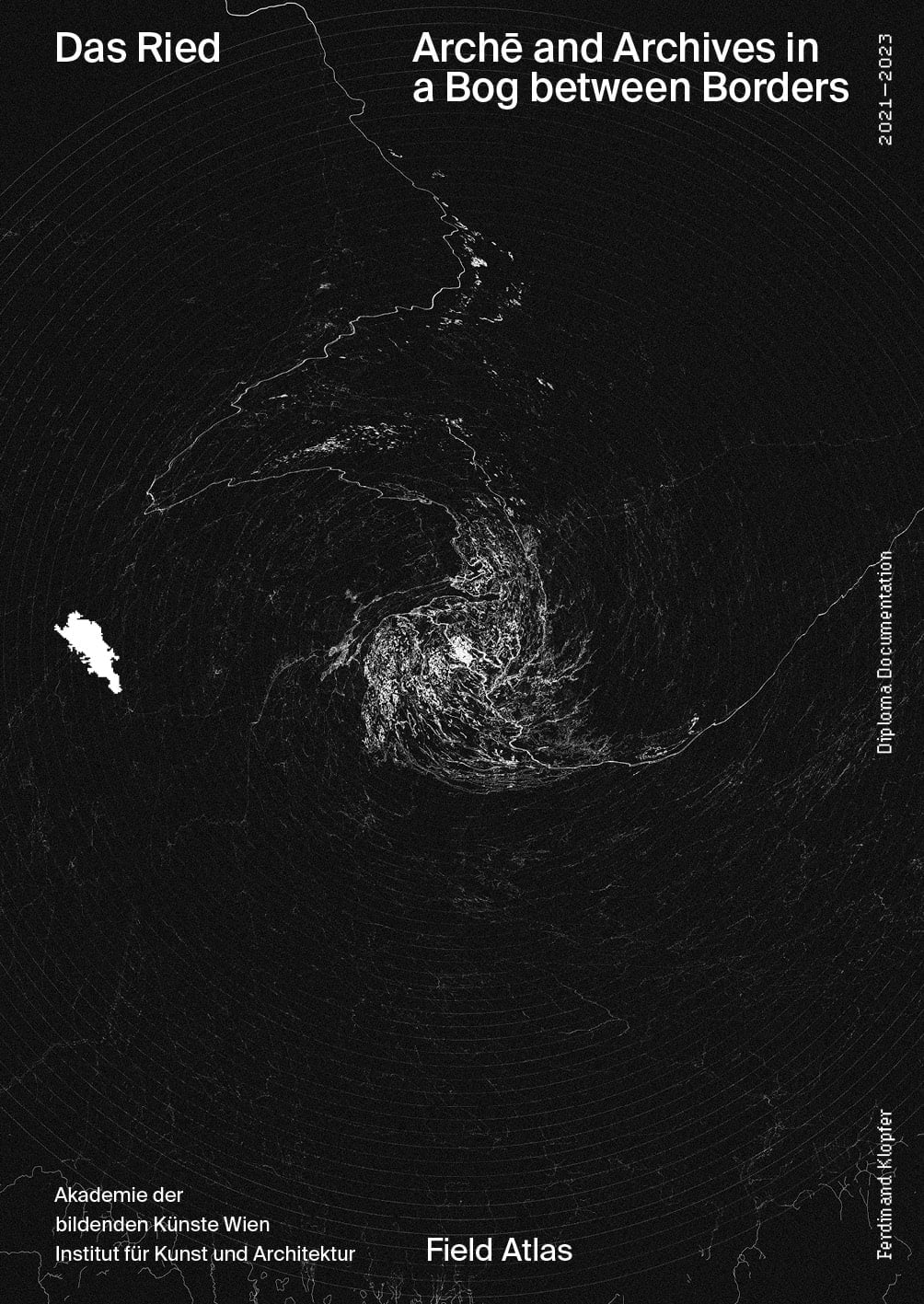

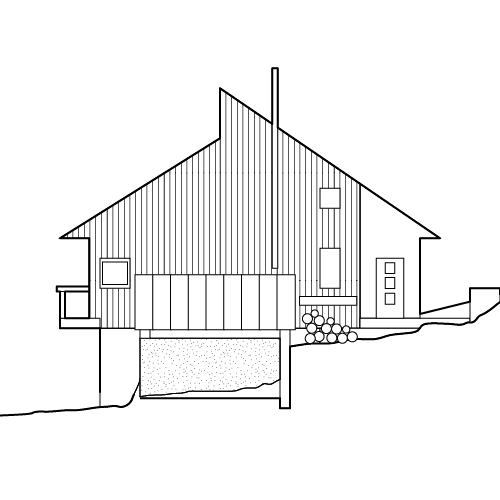

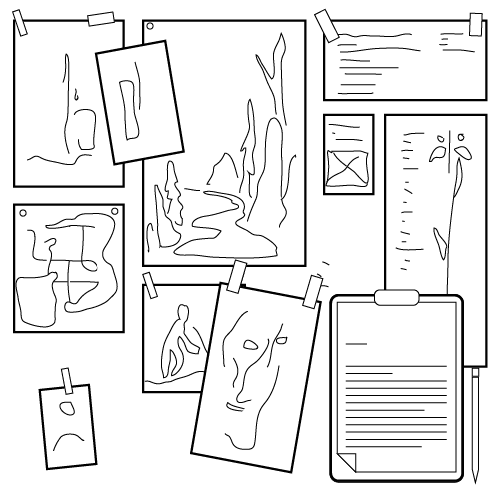

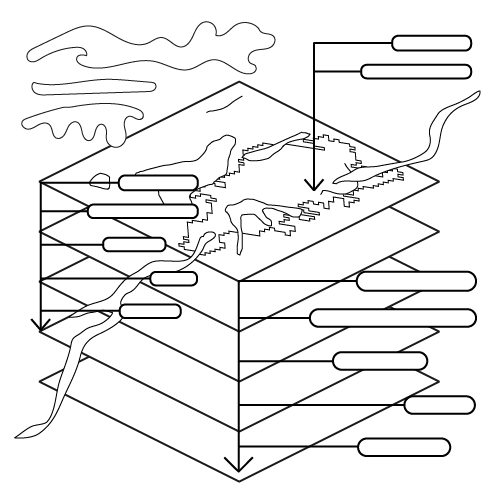

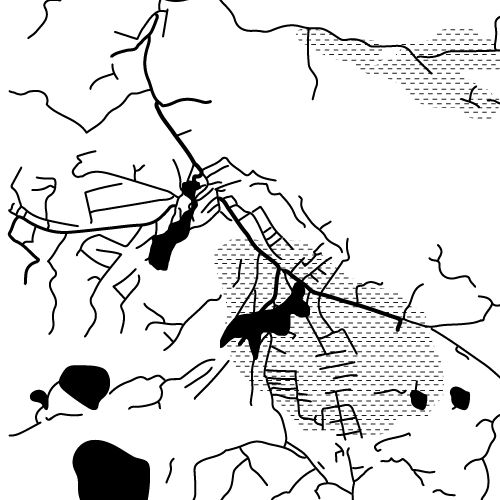

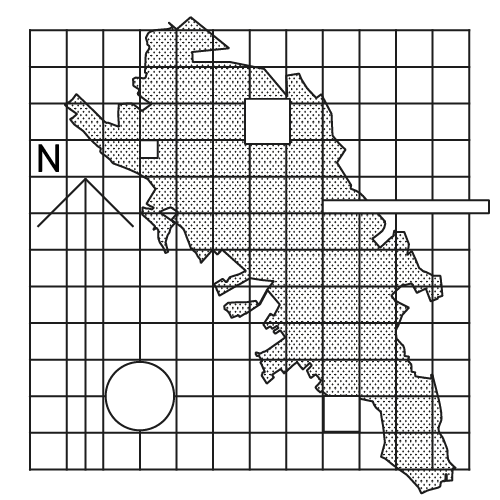

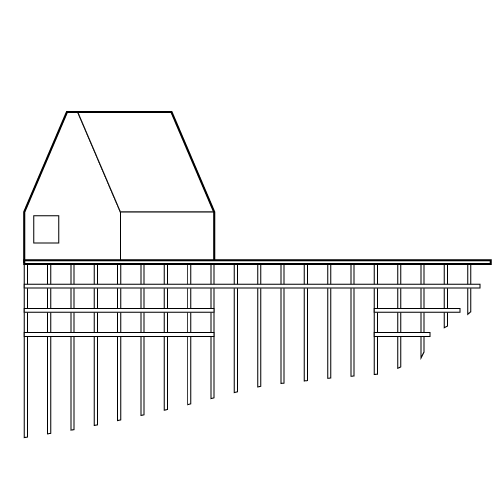

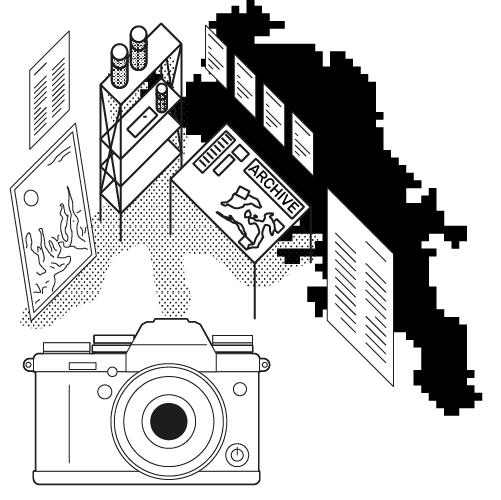

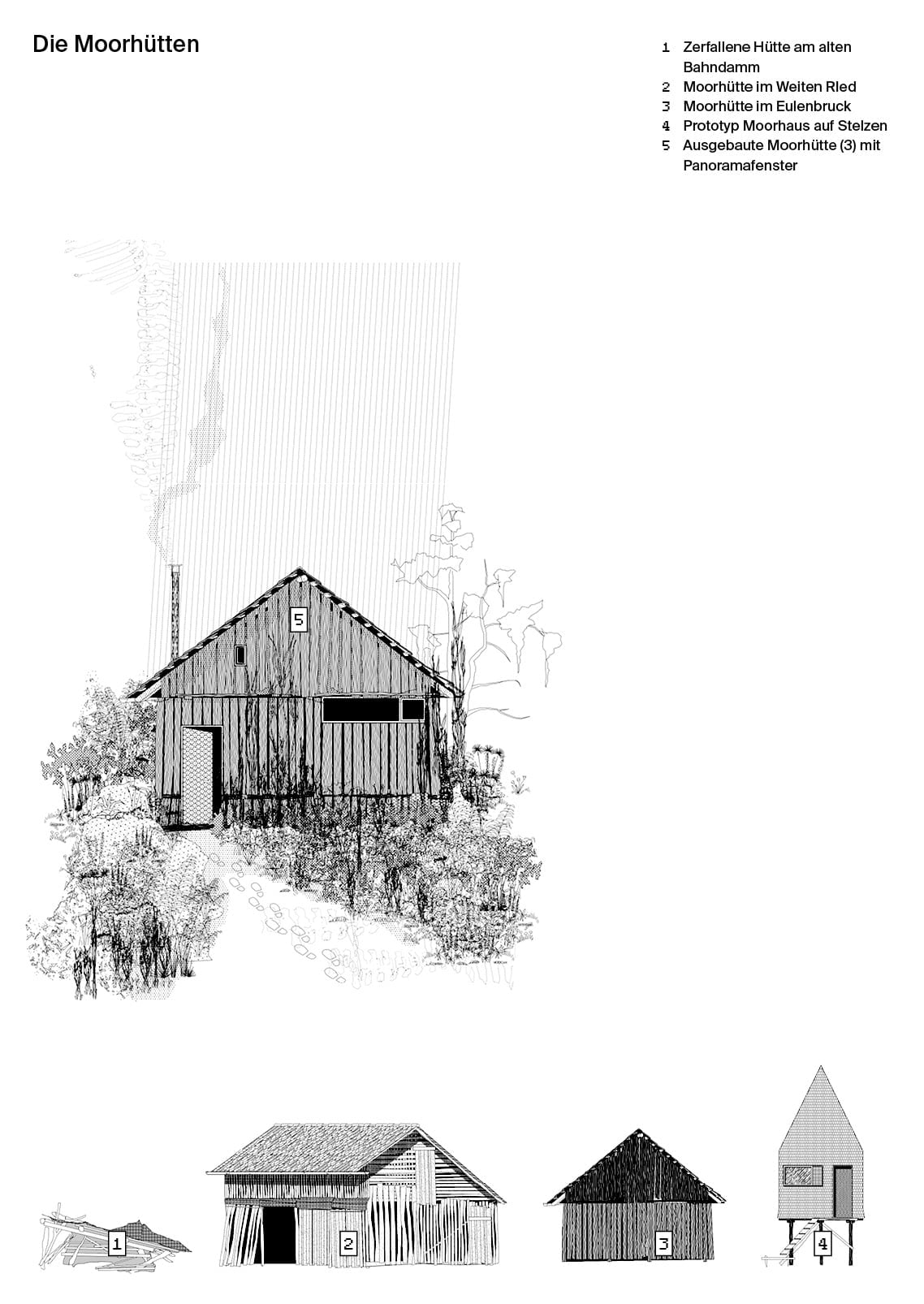

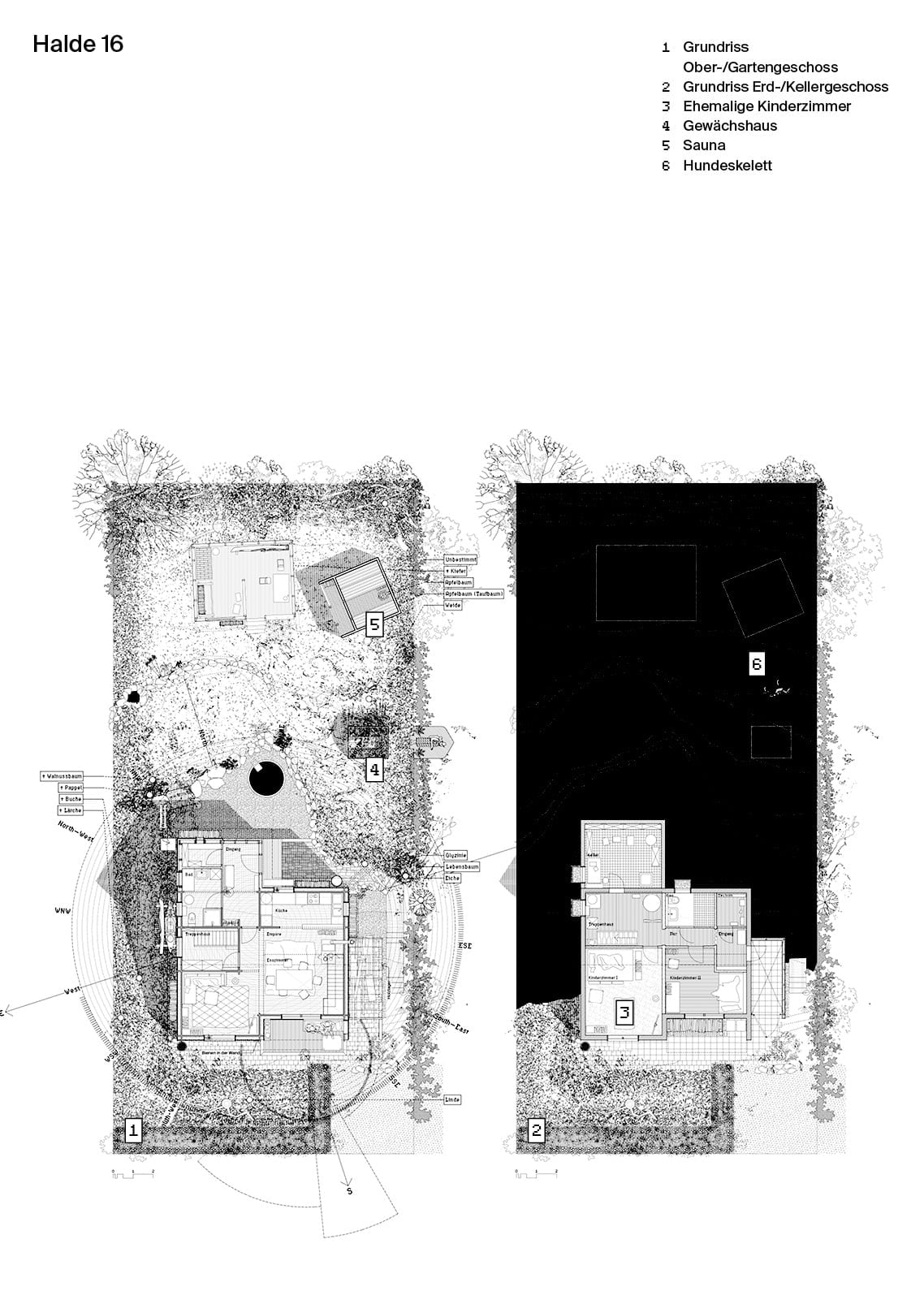

A strange “sense of a place” is certainly something one can feel when entering a bog and thus always existed as a “spirit of a thought” in cultural memory, but it is nevertheless quite difficult to fathom and even find words to describe. How could this ‘spirit’ be approached, deciphered, and translated into a rather architectural language? ‘But what does a moor have to do with architecture?’ — That question was often the first I got asked when elaborating on the thesis project. In the process of mapping and drawing to approach the Ried, profound spatial implications came to light again and again, which are also reflected in the layout of the villages, farmsteads and roads. In a way, the moor seems to elude integration into spatial networks and spatial planning and thus sets a counter-narrative to the built environment. But it also contains a variety of hybrids, transition zones, and interlocking areas where built structures, spatial interventions, and natural forces interact. A question that has occupied me for a long time is how the essence of a place (“Ort”) manifests itself — on the one hand as a physical entity, with a geographical (and even a cosmic) coordinate, a geological and ecological history, and on the other hand, as a mere mental space, a culturally rendered and purely imaginative world, held together through the physics of collective thinking and memory and shared through language and continuous storytelling. This is often evident in the names of the surrounding villages, parcels of land, bodies of water and landscapes, which frequently refer to the moors and marshes that once occupied the depressions of the alpine foreland, but which today exist only as a vague memory through these names. As the research area in question is the place where I grew up and lived allows to approach the moorland also through personal experiences and memories. So while my biography seems to be interwoven with the fabric of the land, it has also captivated countless generations of people since the dawn of humanity. Its deep history ranges from the first human settlements on the shores of the long-gone post-glacial lake, over its transformation into a large bog and its later reclamation and industrial exploitation, to today’s conservation efforts. The moor itself is thus a witness to various stages of civilisation and climatic phases. The project unfolds on several levels of investigation: Initially, it looks at the origins and conditions that once led to the creation of this place, and attempts to trace the dynamic evolution of the natural bodies in a spatial investigation of the bog itself — as a multilayer typology, rich in stories and strange phenomena and as a collective object of anthropogenic modes of land-use and natural forces. Further the project asks how a place is constructed in the sense of connecting an individual human with a landscape and its history, and how this different threads of meaning could be weaved into narration. The particular moorland has been a stage of my own biography, but at the same time it has tended to elude my own “world” – and thus existed mainly on the fringes of consciousness. Its bewildering character disconnects it from social and civilisational realms and creates a sphere of different laws and intentions. But in this sense it bears the possibility to work as a mirror or outpost that observes and reflects the anthropocentric world and thus can offer us to cast a view from an outside perspective onto the human world, we are captivated in. This ability to put oneself in other perspectives and really try to be and think as something else seems to me to be a fundamental condition for ecological thinking. So the following pages shall work as a tool for the reader to imagine the perspectives, time scales, and dreams of entities that differ very much from our selves. This could be a bird seeing the bog as a last refuge in the landscape, a sphagnum moss that is able to lift the whole body of peat towards the sky, or the soil as a multitude of life, death, organic matter, water and minerals, as a witness of countless time periods… Built architecture is always connected to the soil or ground as a foundation. At the beginning of every building activity, the question arises as to the nature and character of the respective soil. Not only does the type of soil shape the form of the architecture, but the architecture will also have an effect on the condition of the soil. In this context, the ground must not be thought of as a static physical state, but as an amorphous entity that is shaped by time and an infinite number of processes, growing or shrinking, and always reflecting human activity on its surface. Since we can imagine the bog as an archive – a device to store, translate and hide stories – the project’s starting point is a form of collecting physical objects, impressions, writings, and sketches. The items that are archived are from manifold resources, containing photographs (Self-made or historic images), botanic samples, textual descriptions, essays, poems, thoughts and scientific sources, Sounds, Visions, Stories, Objects, and so on.

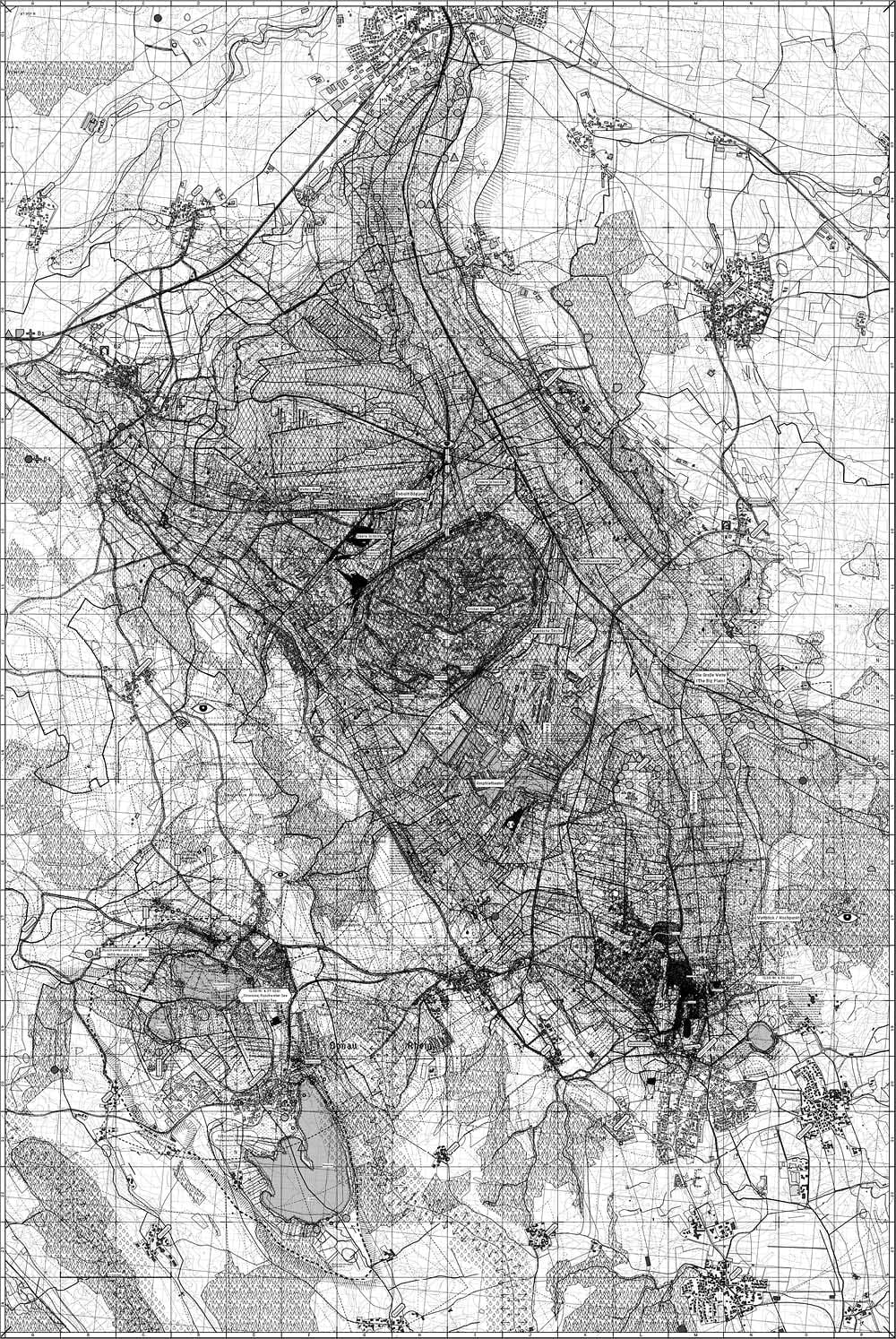

The research started with digging and collecting site-specific research and cartography. The scope of the work is next to the research approach a personal confrontation with the landscape and the terrifying beauty of its individual fragments and particles, stories and phenomenons which often remain hidden in everyday human life. So I was looking for biographical signs and events that took place on a particular ground. The precise research and mapping of one’s own traces embedded in the landscape, work as kind of a reinsurance of our very existence in past times. Maybe it is also a strategy to cope with a looming future that is able to alter every place we know in unprecedented ways. The past and present land use and the anthropogenic influence on the global climate have effects on all environmental phenomenons like the temperature, soil condition, vegetation and fauna, hydrology, and even the geology of the earth’s crust. The work does not claim to provide a scientific exactness or to produce empirical data but sees its contribution more as a connecting element between the different sources of knowledge and research and as an experimental curation of narrative paths leading through the interlocking dimensions of landscape. It is not so much an objective collection and listing of data but a visual interpretation of the discovered phenomenons, with the aim of creating some kind ‘Naturgemälde’, that combines data with emotions – matter and time with a narrative. The project is tries to revive a visual history of this wet-landscape, not as a coherent narrative but “more [as] a meandering thread weaving its way between disparate times and places”, as Stuart McLean formulates it in his consideration of intermediary states of matter in “gelid ,semiliquid, semisolid environments such as bogs, swamps, and marshes [that are] lying on the fringes of human settlement.” Mapping is used here as a graphical encounter with matter and further as a biographic tool, that allows tracing own connections with the land and its aggregates. Analogous to a city, the mapping regards the moor as a complex metabolism of biochemical processes and multi-species interaction and conflicts. The wetland is imagined as a living (or dead) entity that is constantly rebuilding itself, as well as a monument of collective memory, able to grow, shrink and transgress temporal and spatial borders. Its nature as some kind of ‘anti-architecture’ – a structure without foundations, without clear boundaries- constantly changing topography and hydrology – asks what spatial interventions and architectural typologies could be proposed to ensure further regeneration and resilience to an accelerating climate predicament.