Biogeography

“Biogeography” describes an experimental approach to combine Biography (Memories, Stations, Paths and nexus points) with knowledge about Geography and the modes of representation of Cartography.

“The rationality of a grid on a map sinks into what it is supposed to define. Logical purity suddenly finds itself in a bog, and welcomes the unexpected event.”1Smithson, Robert. 1996

Reconstructing own traces

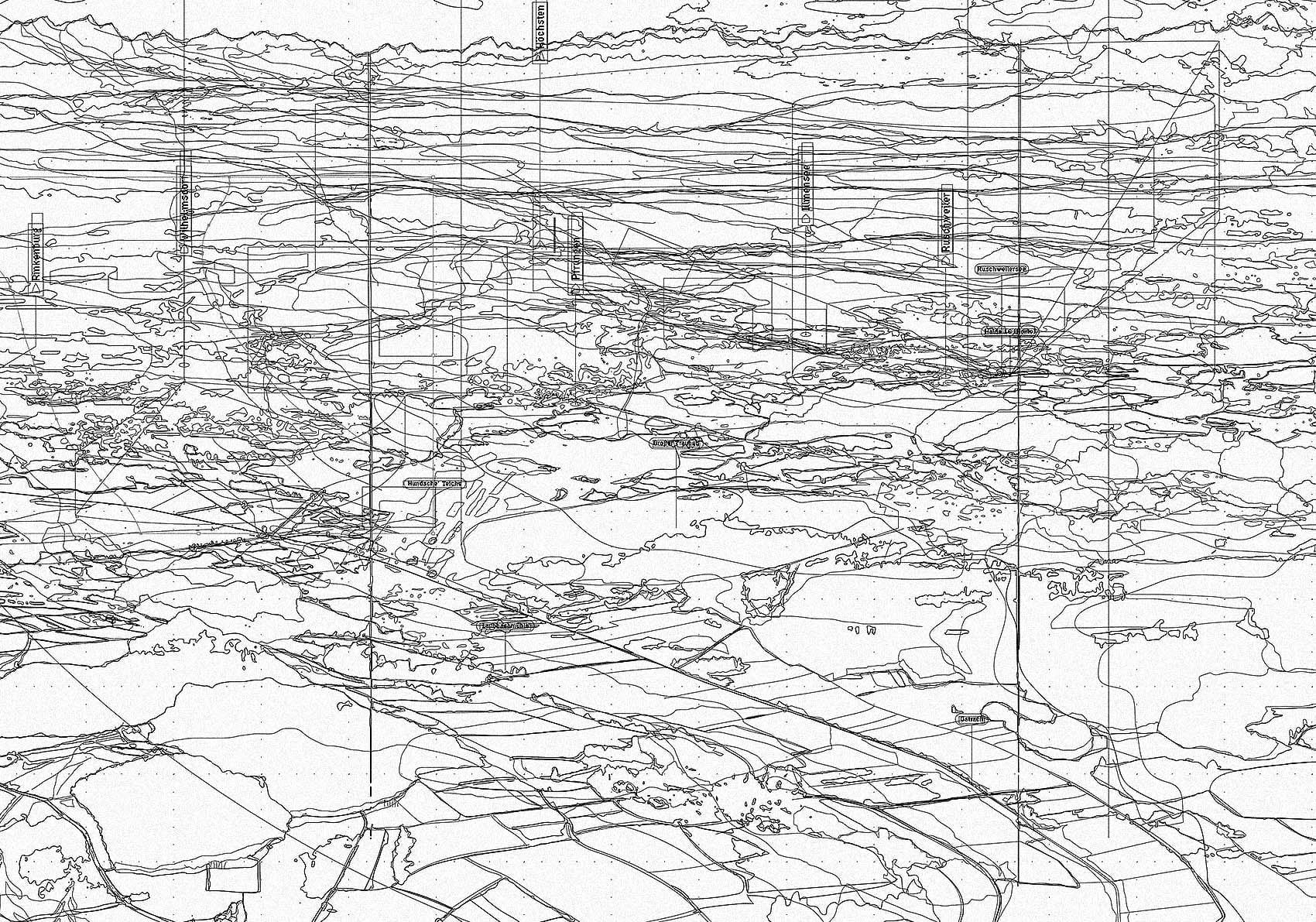

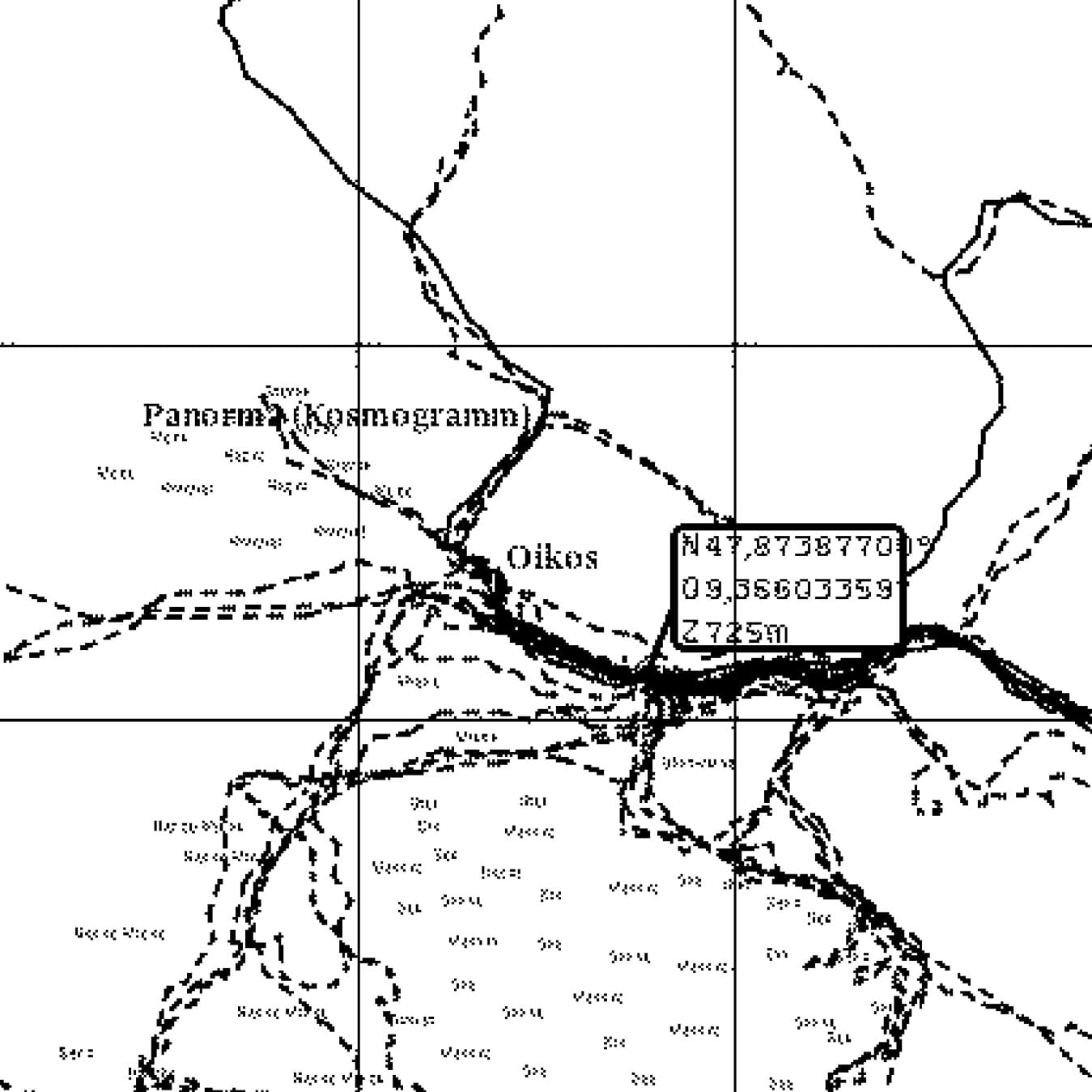

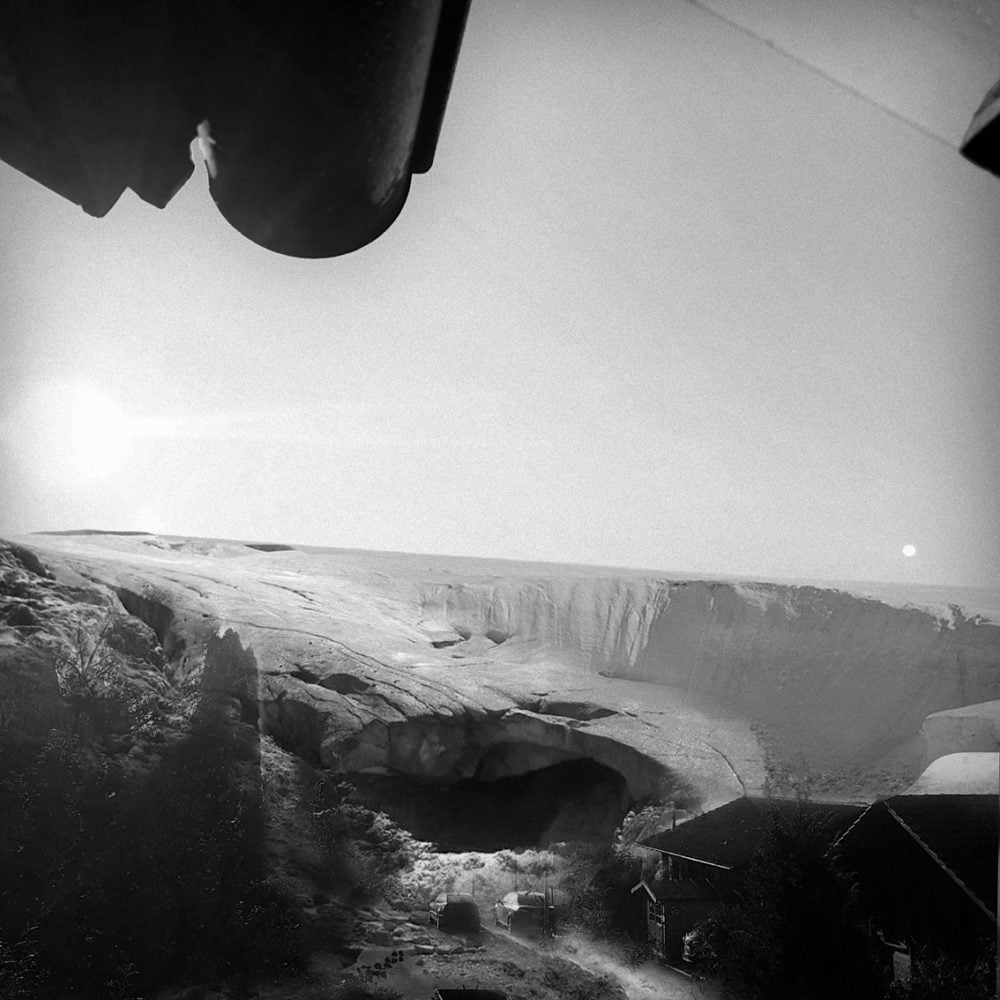

It is strange when you set out to map an area that you think you know well because there are moments when the remembered and reconstructed landscape on the map differ dramatically, or spaces appear that you never noticed before. An initially unconscious intention of the project was a kind of self-affirmation of one’s own existence and past in a certain place, since with the displacement from the area and the sale of the parental home, the physical nodes disappear and the remembered ‘homeland’ also fades out into the fog of vague mental archives. I have spent some of my childhood and youth time in and around the edges of the moors without having given it much thought until now. But the moor itself seems to be a metaphor for a kind of subconscious mind, where thoughts and feelings are stored in the depths to be ‘forgotten’ until something triggers its sudden remembrance, and one is never sure what dark memories might resurface when cutting and unveiling the peat of thought. Thus, a narrative preoccupation with the moor following the analogy of the damp black peat as a matter of memories allows the moor to be understood as a psychoanalytical entrance. It opens up questions such as the role of one’s existence within a ‘home-land-space’, the traces it leaves behind on earth’s surface and the ‘inner landscapes’ we recreate as a mixture of our real-world perceptions, fantasies and desires. What creates the horizons that frame “our” place within a familiar landscape and produce a kind of identification space, and how is it related to its deep past? The bird’s eye view drawings were an approach from a distance to explore the spatial relationship of the two basins (Ried and Illmensee Basin), which worked as biographical stages as well as the ‘private’ horizons that determine the framing limits of the perceived space. It shows the Rieds’ vast plain in the foreground, stretching from its north side to the south where Lake Constance, occurs as a watery horizontal strip, and the towering wall of the Alps constitutes the background scenery. In relation to the Ried the position of my home place appears to be slightly elevated, situated on a gently sloping ridge, alongside a smaller wetland basin and lake group [MT08 Drei—Seen Gebiet: 127], carved out of the Höchsten (Risseiszeitliche Nagelfluh Formation?) I grew up in the small village of Ruschweiler on a sunny slope upon the northern shore of Ruschweilersee, a small but deep ice-time lake embedded in the fen between Höchsten and Judentenberg. While the Ried lies towards its ‘back side’ – an indication that we unconsciously give familiar landscapes a personal sense of their own direction, derived from the topography, the orientation of the house, the sun’s course and the dominant axis and motifs of view. In geologic writing, the overarching Lake Constance region is sometimes described as an amphitheatre: The gradually sloping alpine foreland (audience tiers) runs towards the deep plain of Lake Constance (stage) and is bordered by the alpine wall rising behind it (stage set/scenery panorama). This image is convincing when I remember looking from the balcony at the flickering lightning of a thunderstorm building up over Lake Constance in front of the mountain wall.

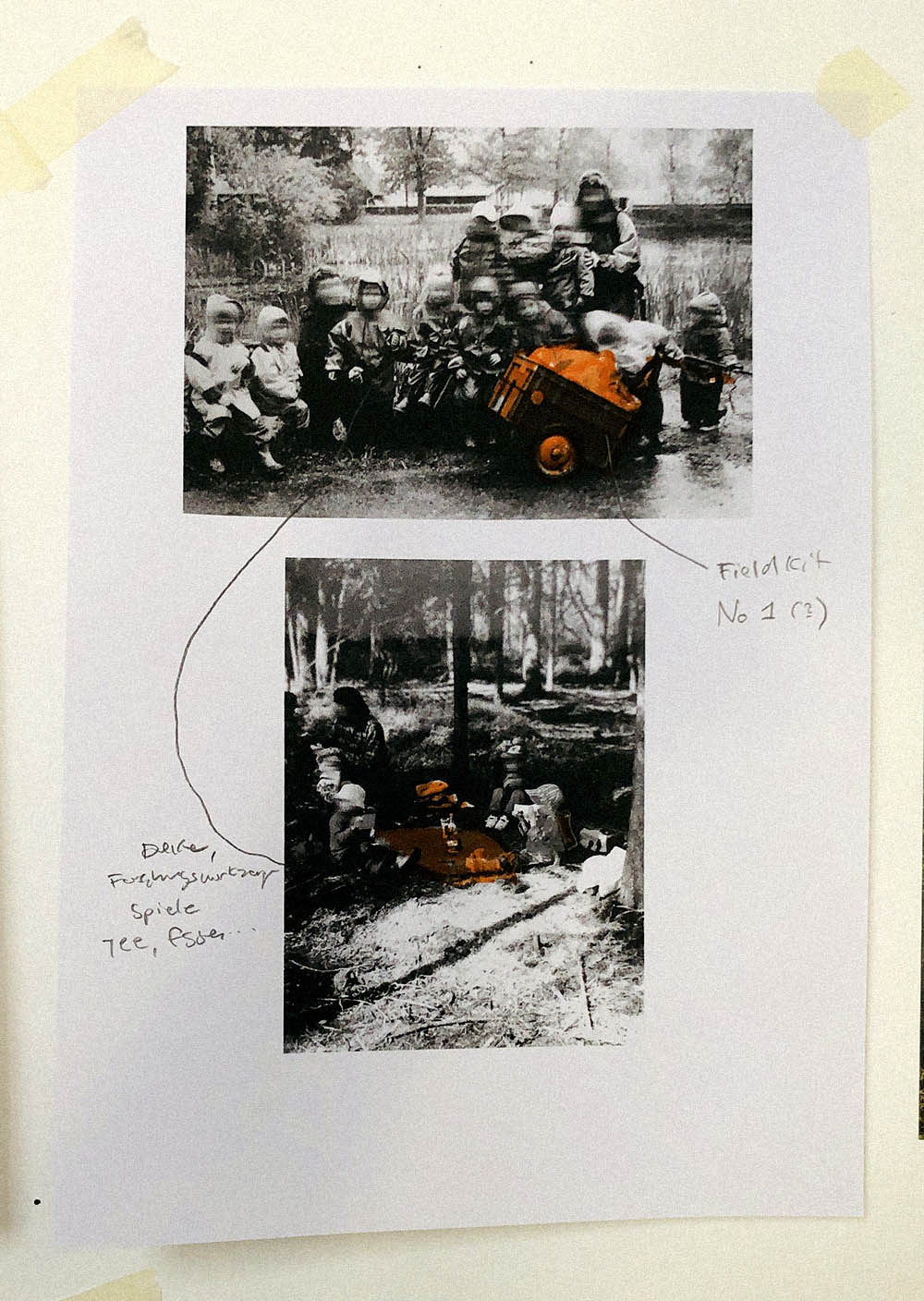

Waldkindergarten and Field–kit No. 1

I first entered the nearby Ried as a small child when I attended the newly founded forest kindergarten, and so I was used to roaming its forest paths and inscribing the impressions awakened by the moor in the cryptic archive of childhood memories. The Kindergarten extended its “garden” and “playground”, so to speak, over the entire southern moorland forests and meadows of Eulenbruck with just a modified construction trailer as a stationary base camp located next to the “Black Sea” („Schwarzes Meer“, a tiny (artificial?) bog pond). The trailer worked as a ‘dry’ and weather-protected assembly point. From there we headed into “the field”, exploring the different spaces of the Ried, and filling them with our own stories and fantasies. On the daily strolls, we were able to enter different environments, experience the change of plant growth and seasons, get up close with birds, mammals, frogs and snakes, and perceive the sound and smell of the sodden past. I still remember feeling, even then, the strange vastness and the desperate pioneering spirit that was once needed to penetrate and colonise the wetland wilderness, and the traces from past times woven into the soil. All the strange discoveries awakened the idea that the world was made up of fantastic places and creatures, as we imagined our own names for individual tree trunks stones, ponds and creeks and integrated them into our plays. Time was marked by experiencing the seasons and the changing garb of nature. Going out and coming back became a daily ritual. For our expeditions, the groups always carried a small hand cart as a “field kit”, which contained a kind of oilcloth as a carpet to create a dry base for resting on the moist bog surface. The handcart also included mugs and teapots, painting utensils, tools, books and handicraft materials. We carried backpacks with our lunch and were equipped with rubber boots and trousers and early had to learn that a space like a moor is probably better entered only with appropriate field equipment in order to be prepared for the sudden changing conditions in soil texture, temperature, moisture and weather.

After kindergarten, I moved back from the Ried to Illmensee primary school, situated at the shore of the big lake in the elevated fen plateau, where I discovered another form of wetland in countless strolls along the forests and water bodies. Only in retrospect did I realise what a privilege it was to grow up in such a landscape, which, with the knowledge of all the ecological crises and destruction in the world, is now appearing as a kind of paradisical ideal. The entrance to the Gymnasium led me back to the Ried. At that time, my classmates and I somehow perceived the Ried as a secret garden behind the school where one could hide in the misty woods to disappear from sight and be able to do “forbidden” things so that entering the Ried always seemed to mean stepping out of the social orders and rulebooks into a rather archaic realm. So in retrospect the landscape in which one grows up as a small child seems to be initially taken as an ideal image or prototype that is extrapolated into a concept of the (whole) world. Its characteristics and peculiarities and the lessons learned from it are glowing as some kind of background radiation under all later experiences and perceptions. Especially with regard to the current situation with reinforcing global crises and transgression of tipping points – with the possibility of the destruction of all we know – these memories are transfigured as a kind of idealized paradise image of an ‘intact world’, but which in turn can serve as a source of hope and resources for coping with the situation and even find strategies to preserve the fragile beauty of the Ried.

Mapping as a tool of remembrance

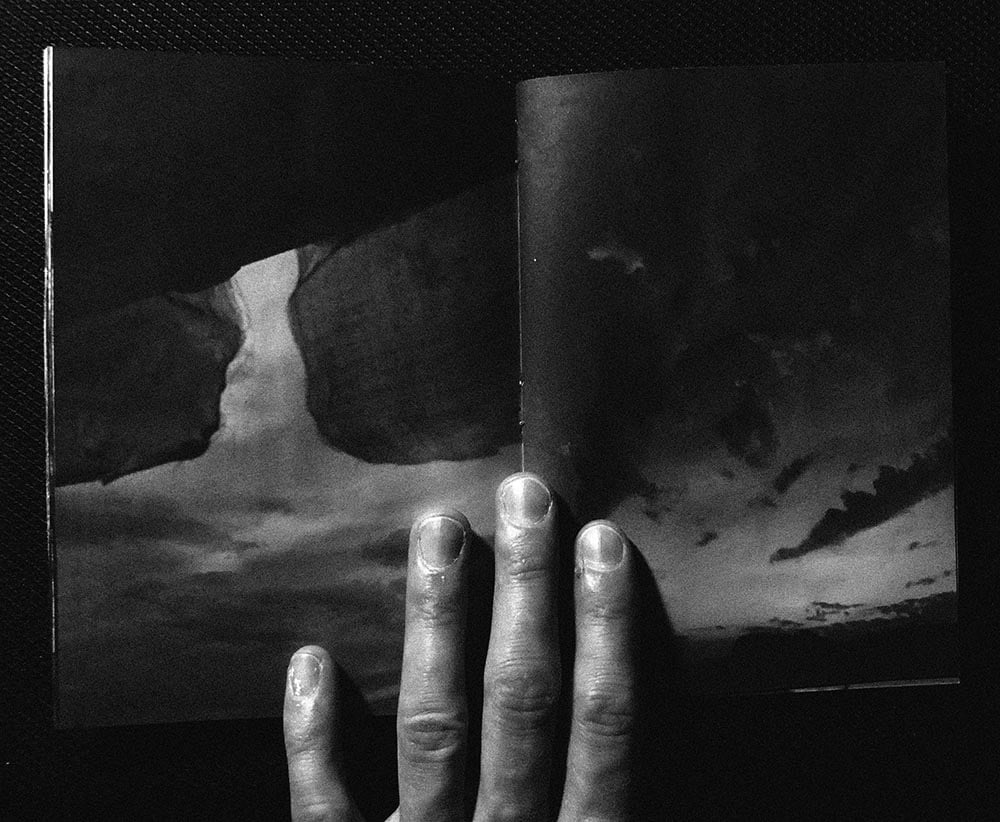

The method of (repetitive) walking – moving ones body along an invisible path between coordinates following the topography – can be understood as a practice of drawing onto the landscape as well as reading its stories while permeating different atmospheres, spaces, thresholds and horizons. Are these forays and routes repeated again and again a trail gets engraved onto the respective surface, the soil gets condensed and vegetation retreats partly so a trace starts to appear, but it also leaves a sequence of spatial impressions that burn as memories into ones mind. Landscape seems to be perceived and constructed as imaginary scenery, we can access in our mind, mainly by the body moving through it. By walking through a landscape we constantly rearrange the relation of our body to the natural bodies and objects that frame this respective world. Here we observe the changed emotions when, for example, we are standing on a hill and can look over and survey the vastness of the bog from a distance, or whether we are situated at the bottom of a valley, enclosed with dense seams of trees, and the feeling that we are just floating over the water surface of the long-gone lake. Since I was born in 1992, 30 cycles of the seasons have already happened and about 30mm of peat layer could theoretically have been gained in the still functioning raised bog areas. The mappings can to some extent be understood as a journal in which the entries are not filed in chronological order, but are drawn in a spatial “juxtaposition” with temporal simultaneity. When looking at a certain coordinate on the map, a multitude of temporally displaced events can be “remembered” and collapsed into a singular gesture. Thus the maps here are less as a neutral guide to ‘real places’ than as a personal path to access and revoke the memories stored in relation to the landscapes, and it was interesting to observe how the simplest abstract shapes – a polygon describing a lake, a line describing a pledge, or a rectangle describing a house – evoke rich imaginings and feelings that in turn triggered the next steps of the drawing. In this way, one gets into a feedback loop of strange momentums where memories and their graphic abstraction reinforce and multiply each other. A vague childhood memory of a local walk can be translated into a fragile polygon in mapping: One starts from a certain place roams around and sometimes touches other worlds to finally return to the point of origin. Through this daily practice, the idea of one’s own life world emerges over time, and the boundaries of ‘behind’ and ‘outside’ shift further outwards.

Familiar Horizons and the House as Archive

When I travelled back to investigate the moor, I also tried to fathom the strange feelings evoked by entering (and finally leaving) home – a place one has known and observed over a period of time, but also something that lies behind, dedicated to irreversible dissolution. In order to gain an understanding of the spatial nature evoked by such feelings I reconstructed and mapped the places and horizons, that contained, produced, and framed the biographical spaces I once used to live in. While growing up, one first observes and interprets the world that surrounds us as a background framework (constructed of places, sights, barriers, air and light, matter and materials, …) in which our life unfolds, evolves and interweaves complex narratives. So in a way, we translate the spatial characteristics and topographical features of these individual environments into a mental map of one’s own world. The landscape provides the spaces in which we learn to live and think and at the same time serves as a location within a vast global system, that creates a certain sense of position and identity. This mentally constructed inner landscape that we think of as home and separate from other places on earth, is formed by a set of horizons – in the sense of imaginary lines that imply a before and behind.

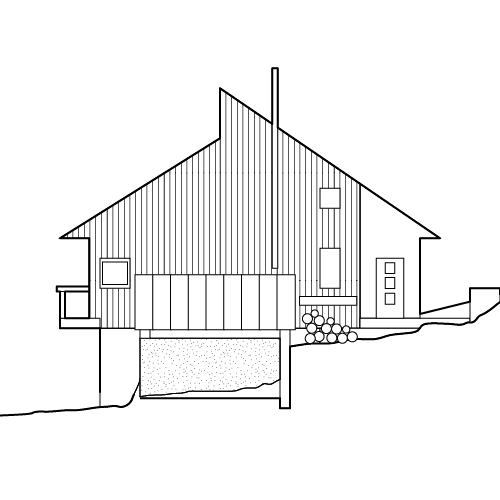

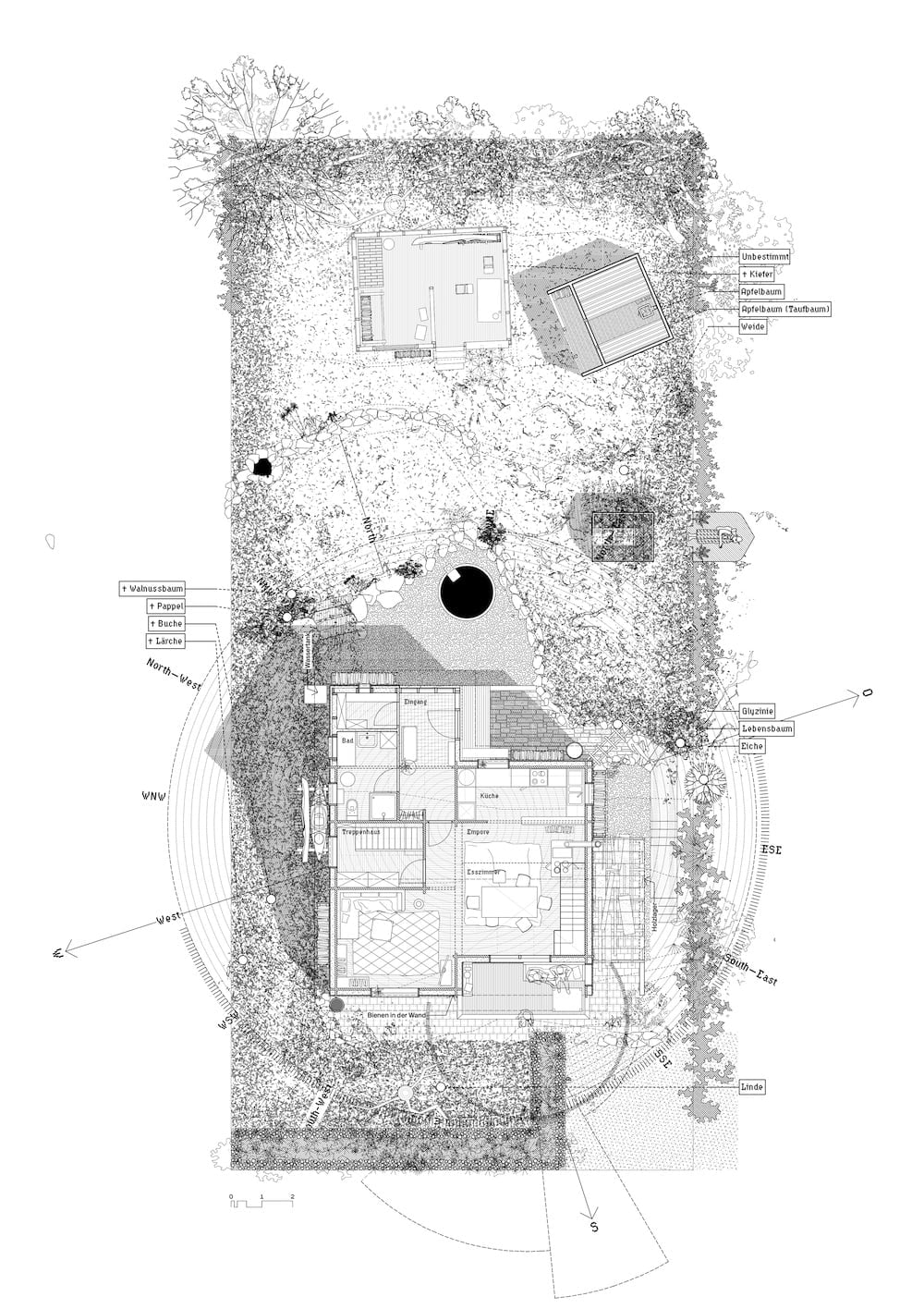

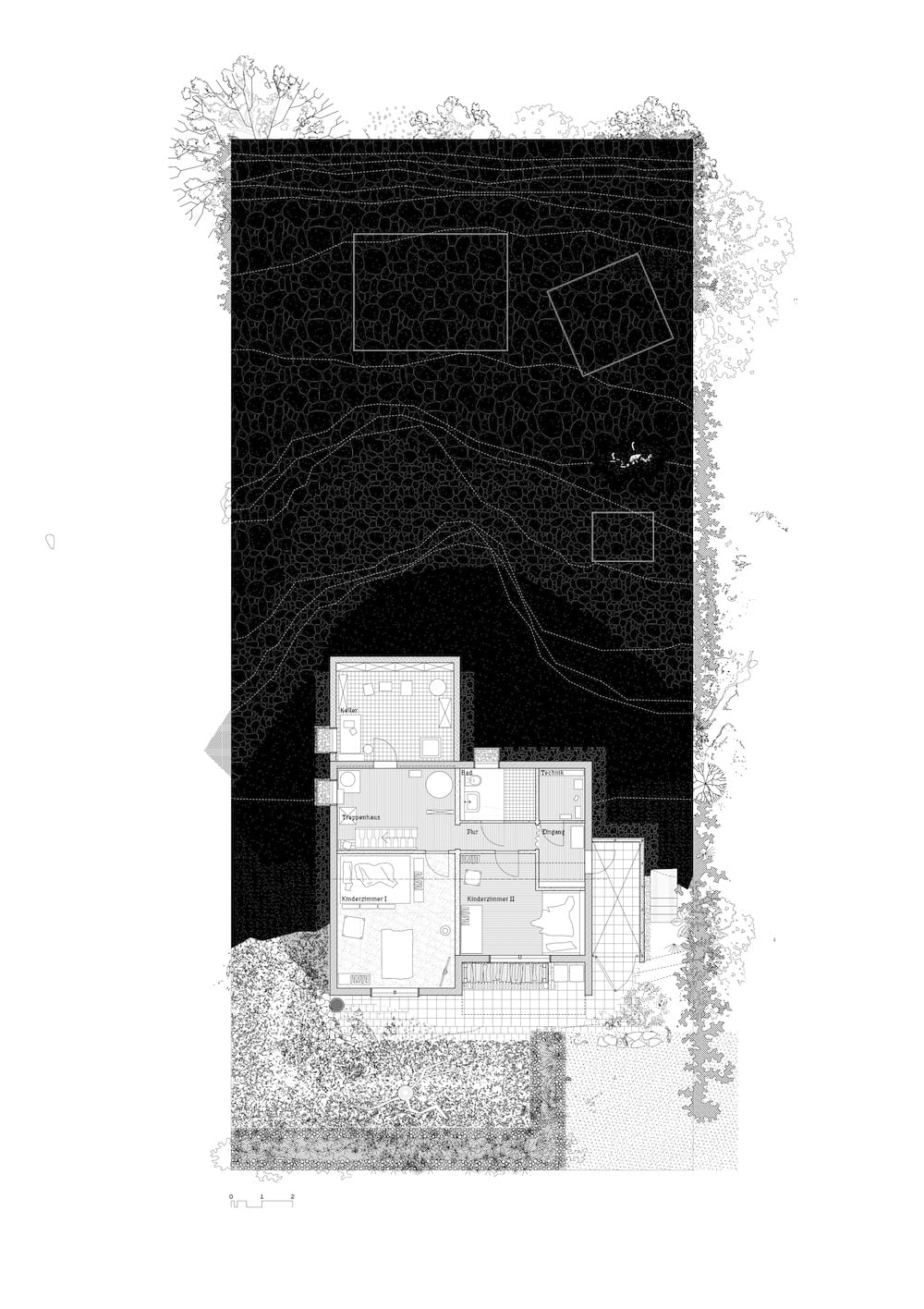

The house I grew up in is part of a former holiday settlement (referring to the nearby lake sites), consisting of simple solid wood log cabins arranged in three rows. The settlement was built in the 1980s (?) on the western margin of Ruschweiler and lies downhill from the main road to Pfullendorf. The rows of houses run parallel to the shoreline of Lake Ruschweiler and thus face south – towards Lake Constance and the Alps.

Gradually, the cottages were also sold and from then on permanently inhabited, resulting in a strange pattern of inhabited and mostly empty houses. The house also reproduces the previously described functions of an archive on a smaller scale and forms the spatial stage for living spaces and narratives. It grows with its inhabitants and is shaped by their design interventions. (In our case, the existing log cabin structure was broken up and extended with an offset pent roof.) In this case, there is once a “real”, built and inhabited house that has absorbed the memories in its material fabric and thus archives information in a concrete position. By moving out and selling the house last year, a further initial state (Archē) for appropriation and redesign is initiated which means that one‘s own traces are increasingly vanishing, as well as the accessibility for oneself. In the end, the personal physical “built” archive disappears for me, but the memories transgress into mental archives. Through the floor plans, memories can be evoked and reactivated, and especially the spatial narrative that once happened there can be made visible. Already in the enclosed cosmos of the garden, one can observe the effect of time on the course of natural progression. As one gets older, the vegetation also grows up and dies in some places. Shrubs grow taller, old trees go and new ones are planted. The snow in winter seems to get less and less and a frozen lake is an exception today while it occurred still often in my childhood – a sign that even these inconspicuous places in the Hinterland are part of a global atmosphere and its ever faster-changing conditions.

[to be edited/continued…]