Circular Garden

Hortus Conclusus

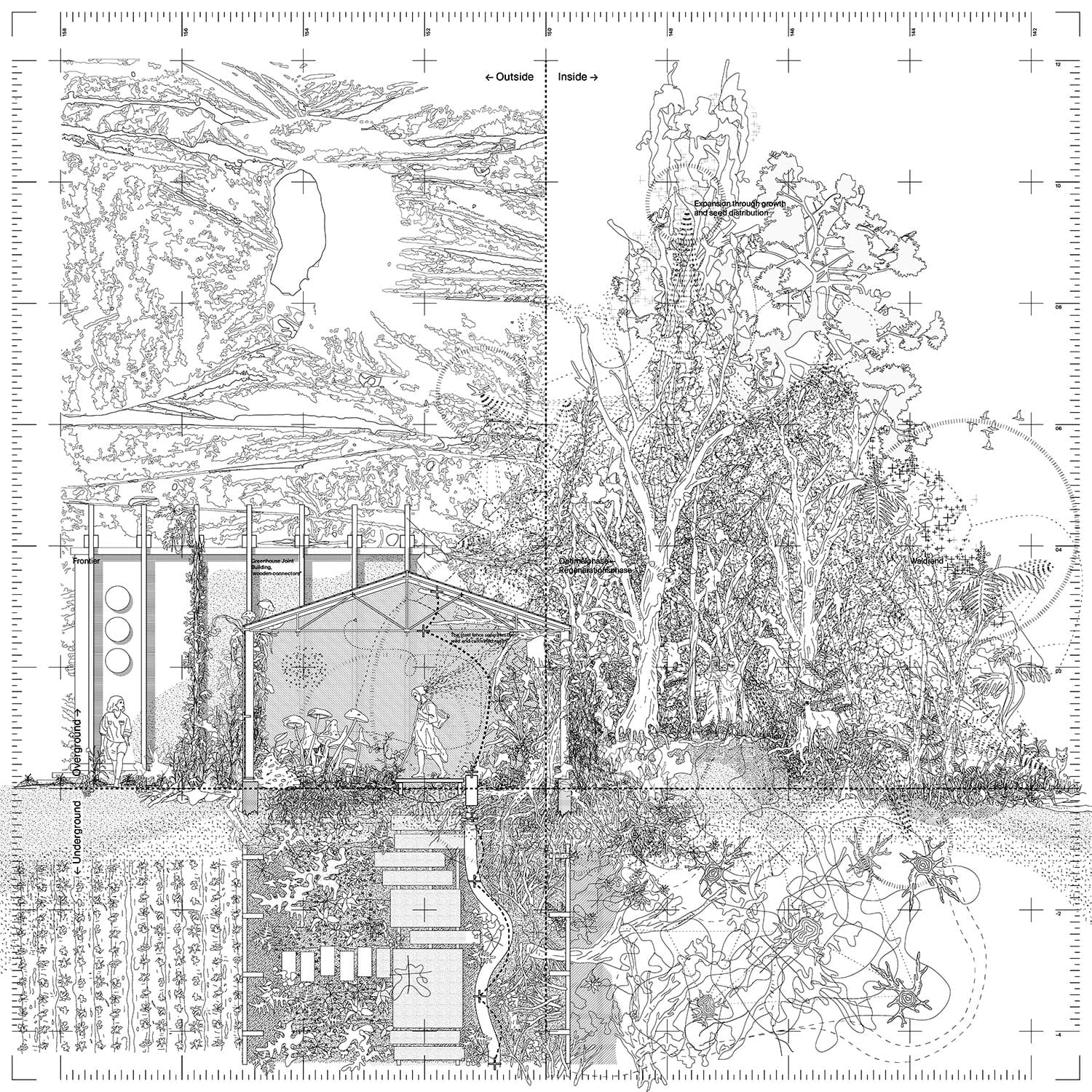

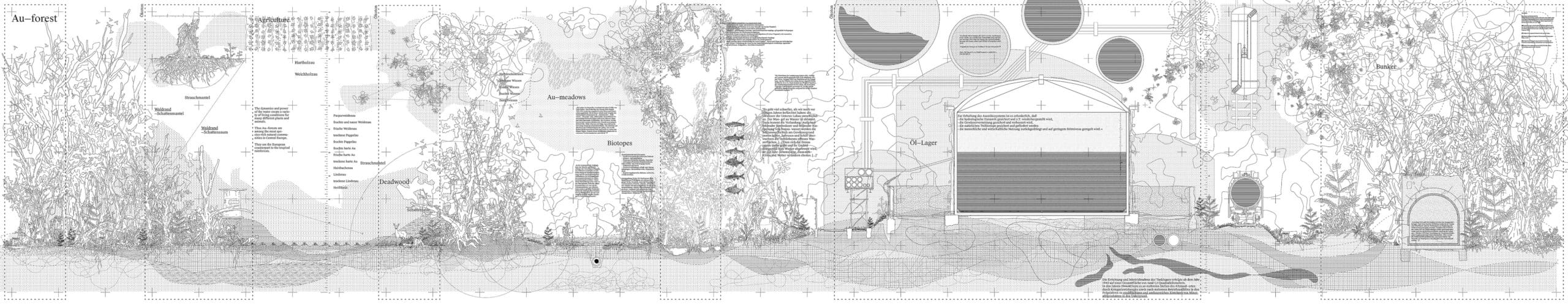

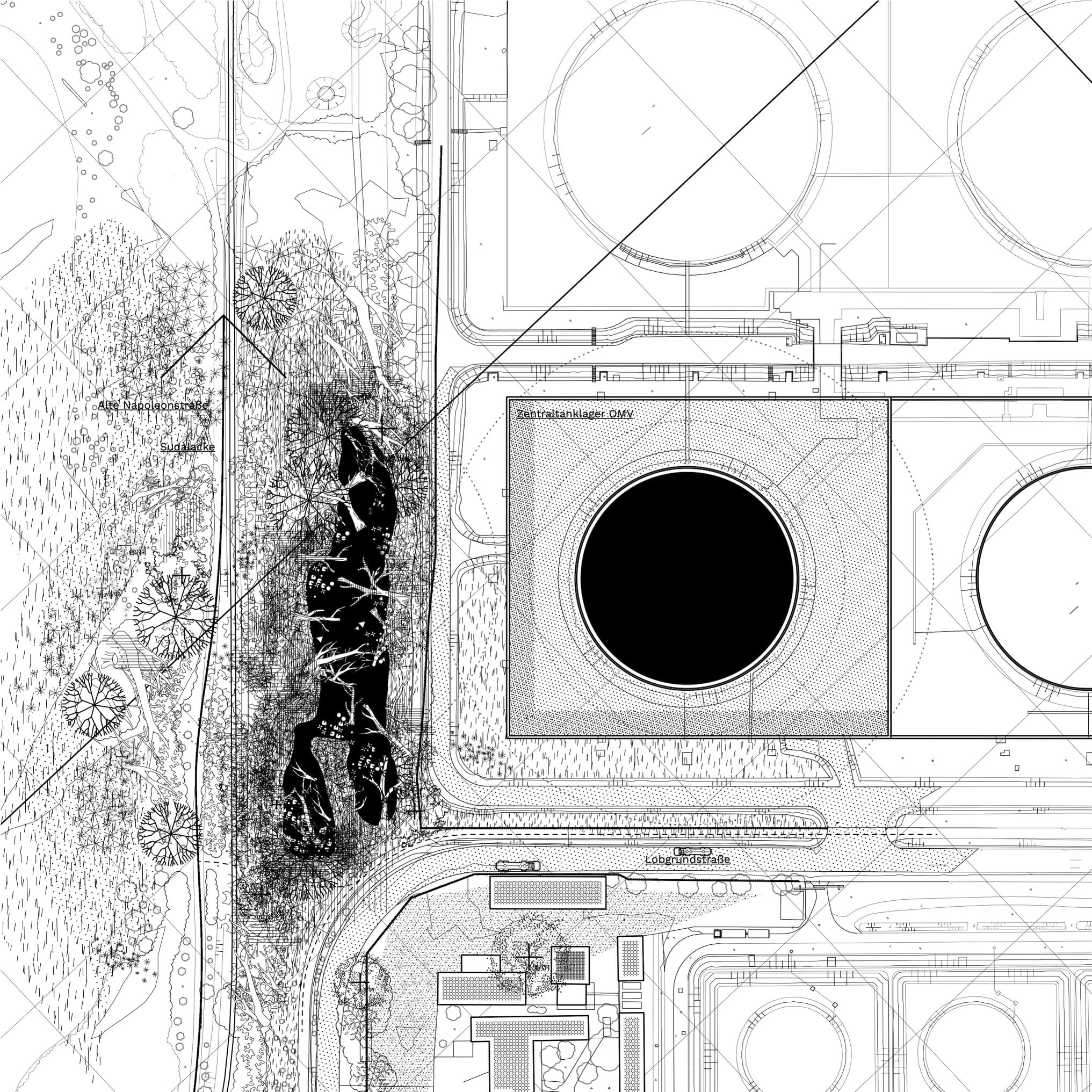

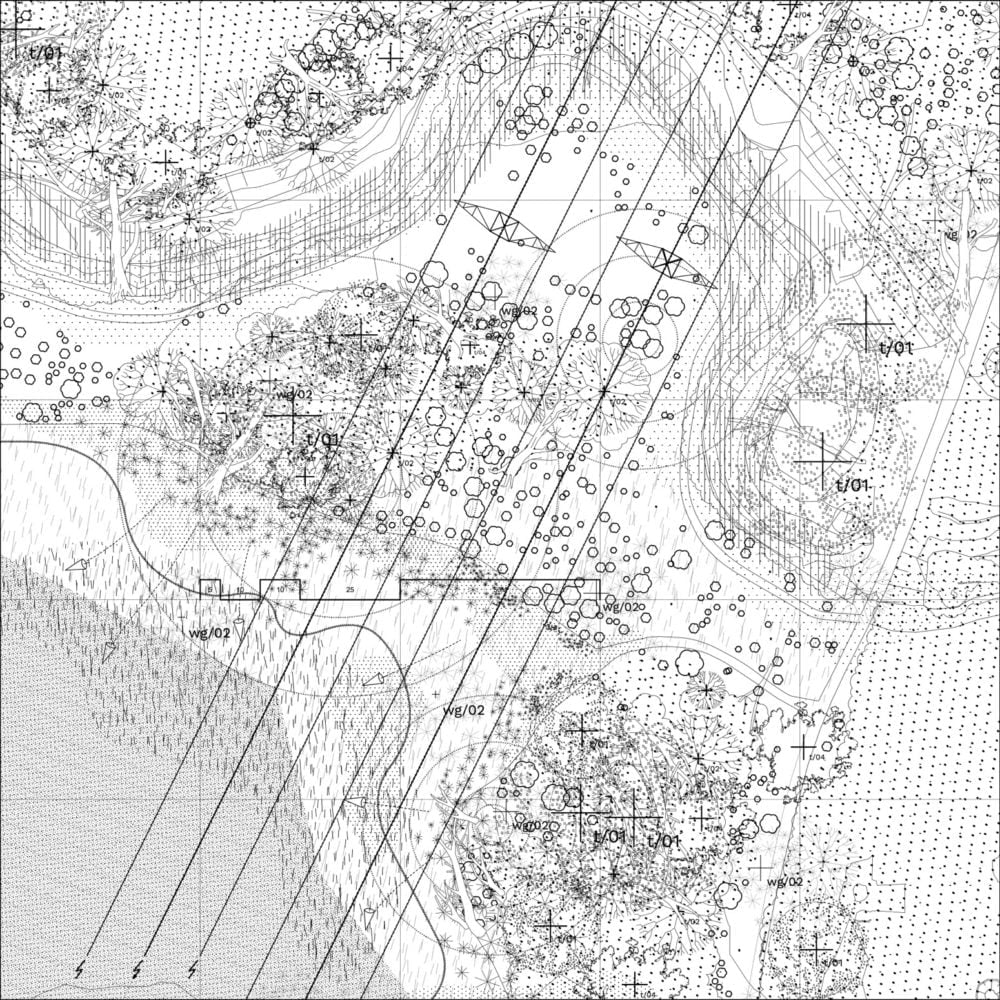

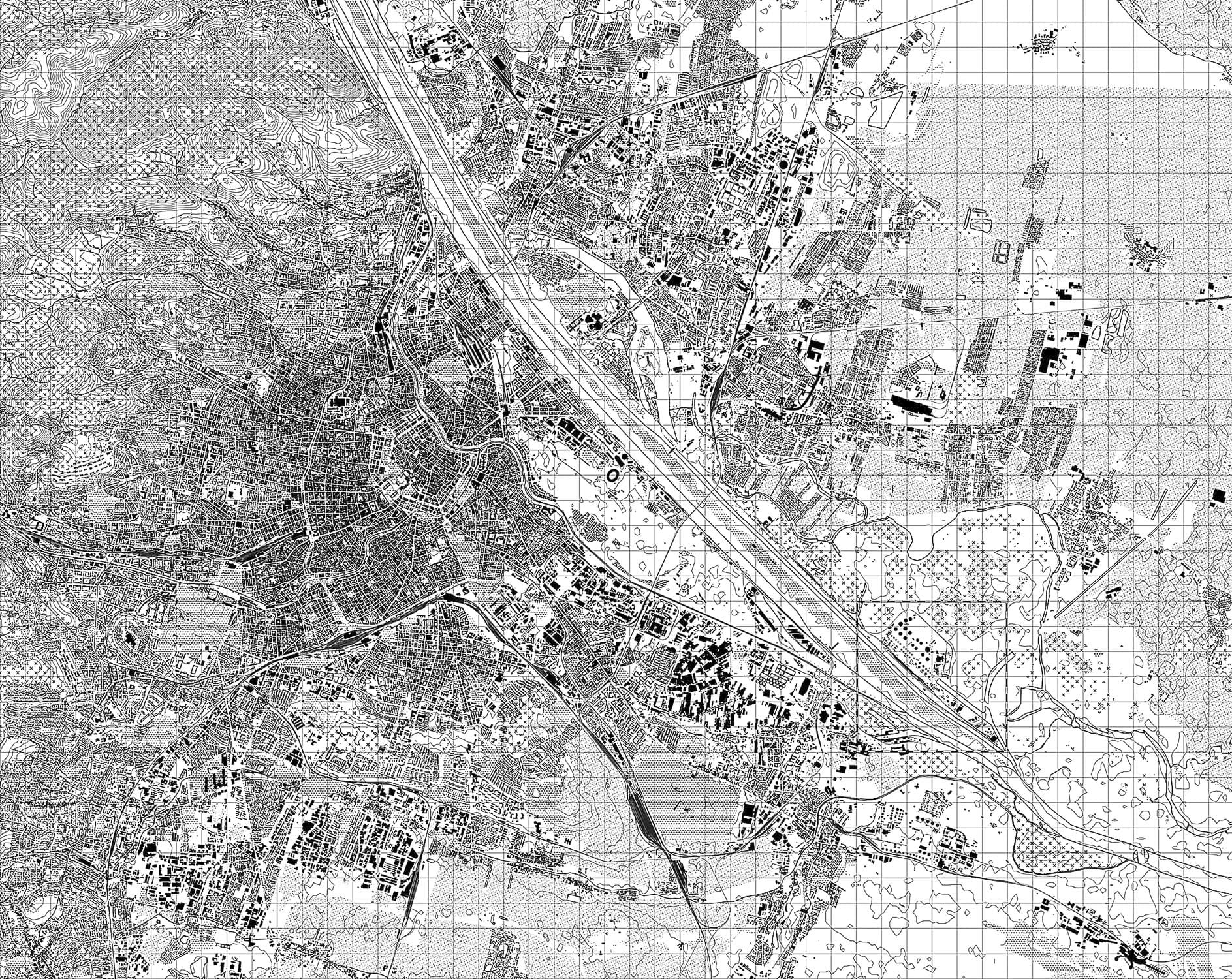

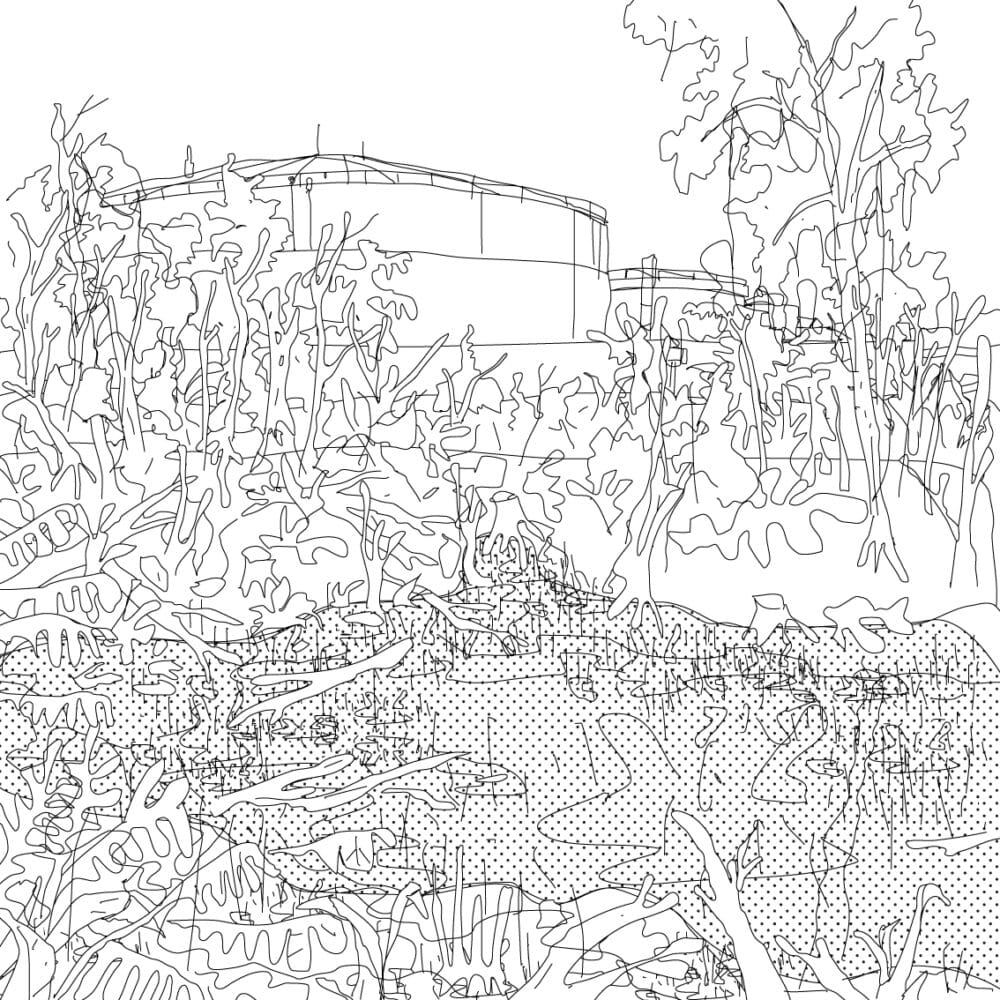

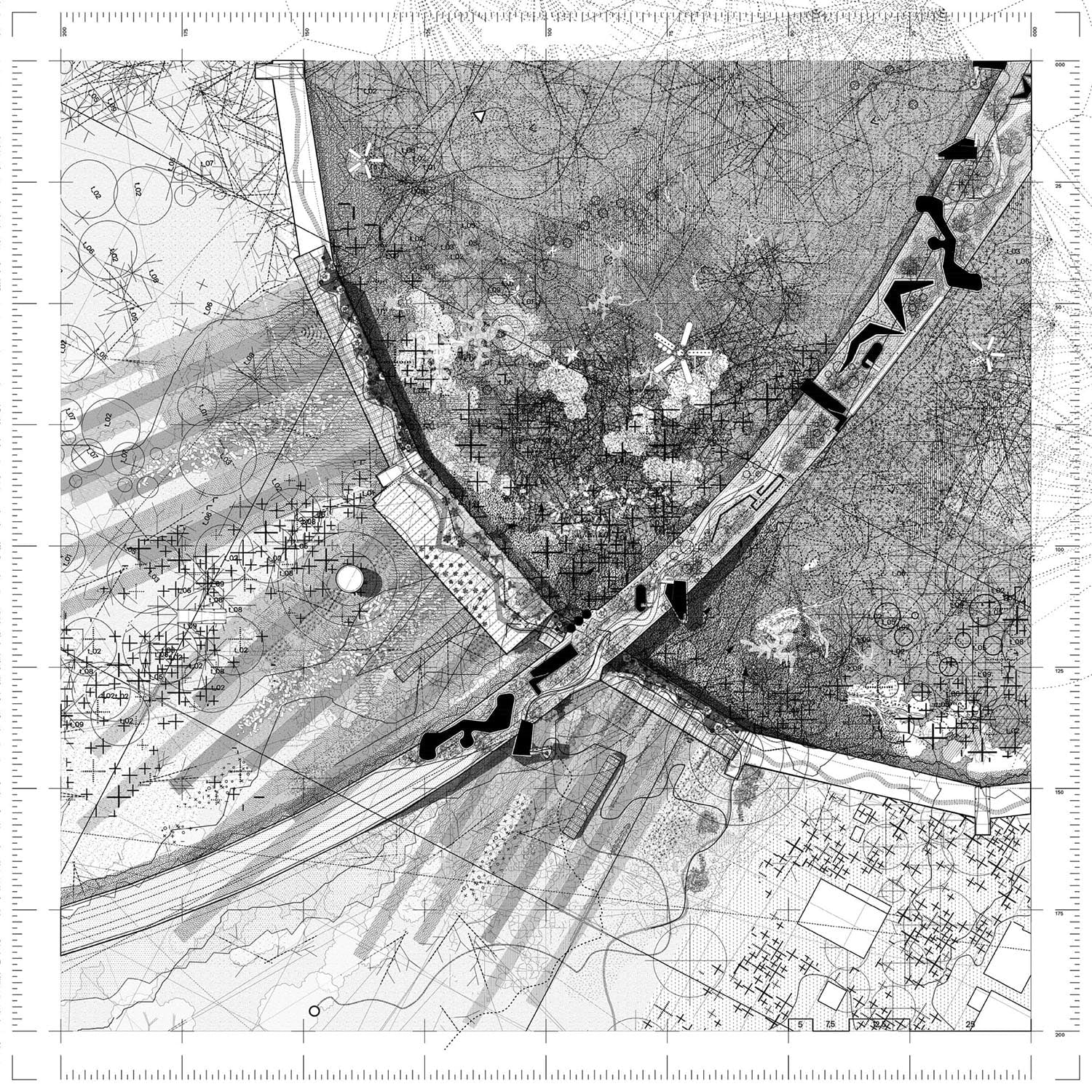

Das Projekt begann mit der Erforschung und Kartierung eines gigantischen Öllagers in den Donau-Auen am Rande Wiens. Hier traten die Kontraste zwischen der ausgelagerten städtischen Infrastruktur und hybriden industriellen Strukturen sowie den Überbleibseln der einst wilden Donau-Auenlandschaft – lange vor ihrer Begradigung – deutlich zutage. Besonders auffällig war ein architektonisches Motiv des Speichers: geometrische Strukturen (Kreis/Zylinder) zur Speicherung eines Volumens archivierter Energie (Erdöl, Benzin usw.), das für die Funktionsweise einer lebendigen Stadt unerlässlich zu sein scheint. Doch auch die Tümpel entlang des Areals – Überbleibsel der einst paradiesischen Auen – dienten als Speicher: für Biodiversität, für die Vielfalt des Lebendigen und für all die unscheinbaren Prozesse und Organismen, die letztendlich unser Leben auf der Erde ermöglichen. Die Ergebnisse dieser Recherche wurden auf einen anderen, zugewiesenen Ort projiziert: Auf einem Brachland in der Peripherie der wachsenden Stadt Wien, nahe der U2-Station Aspernstraße, entwickelte ich den Entwurf eines Hortus Conclusus.

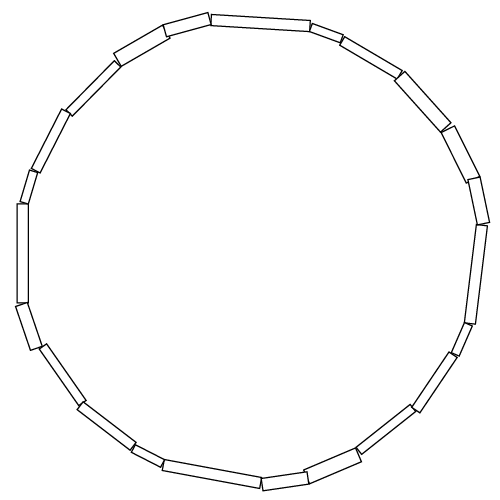

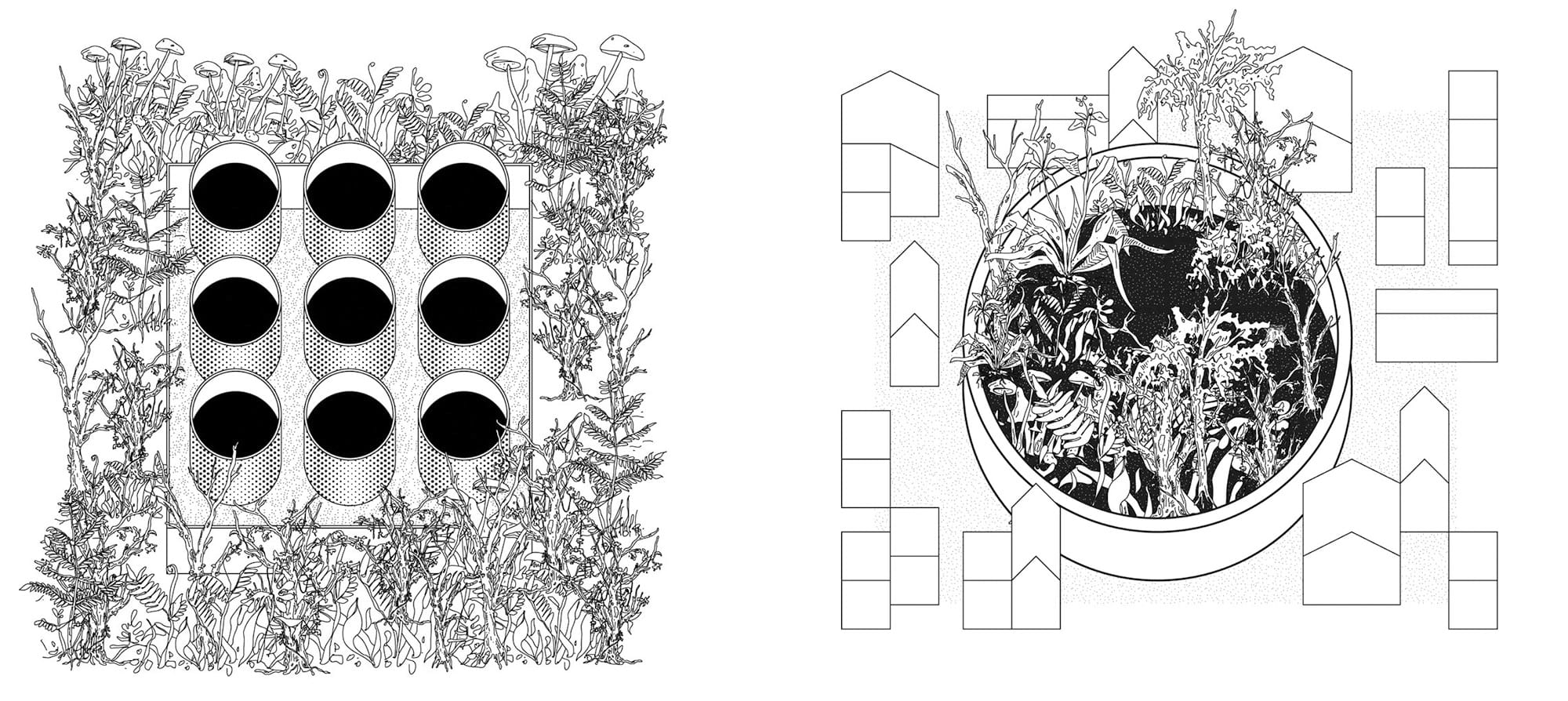

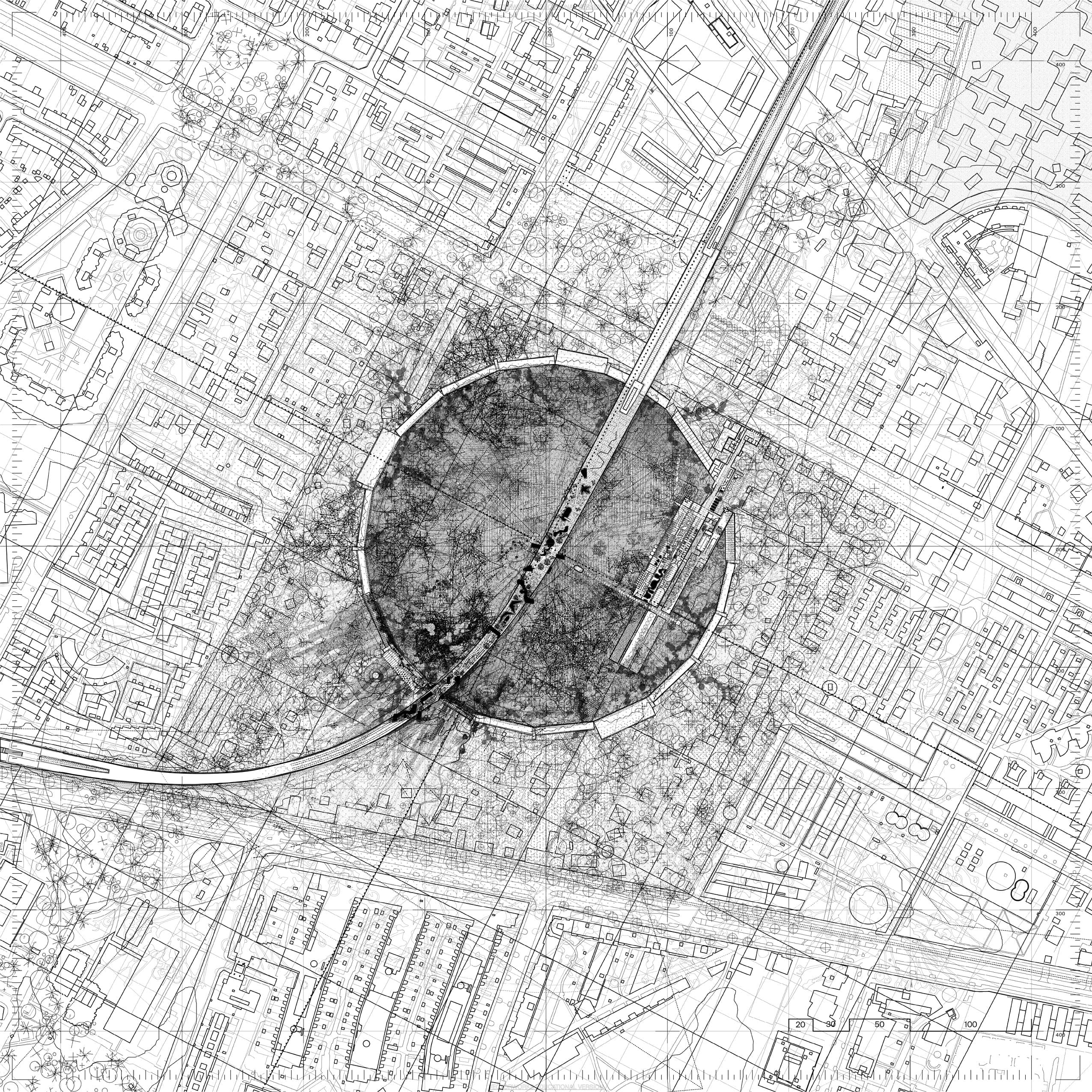

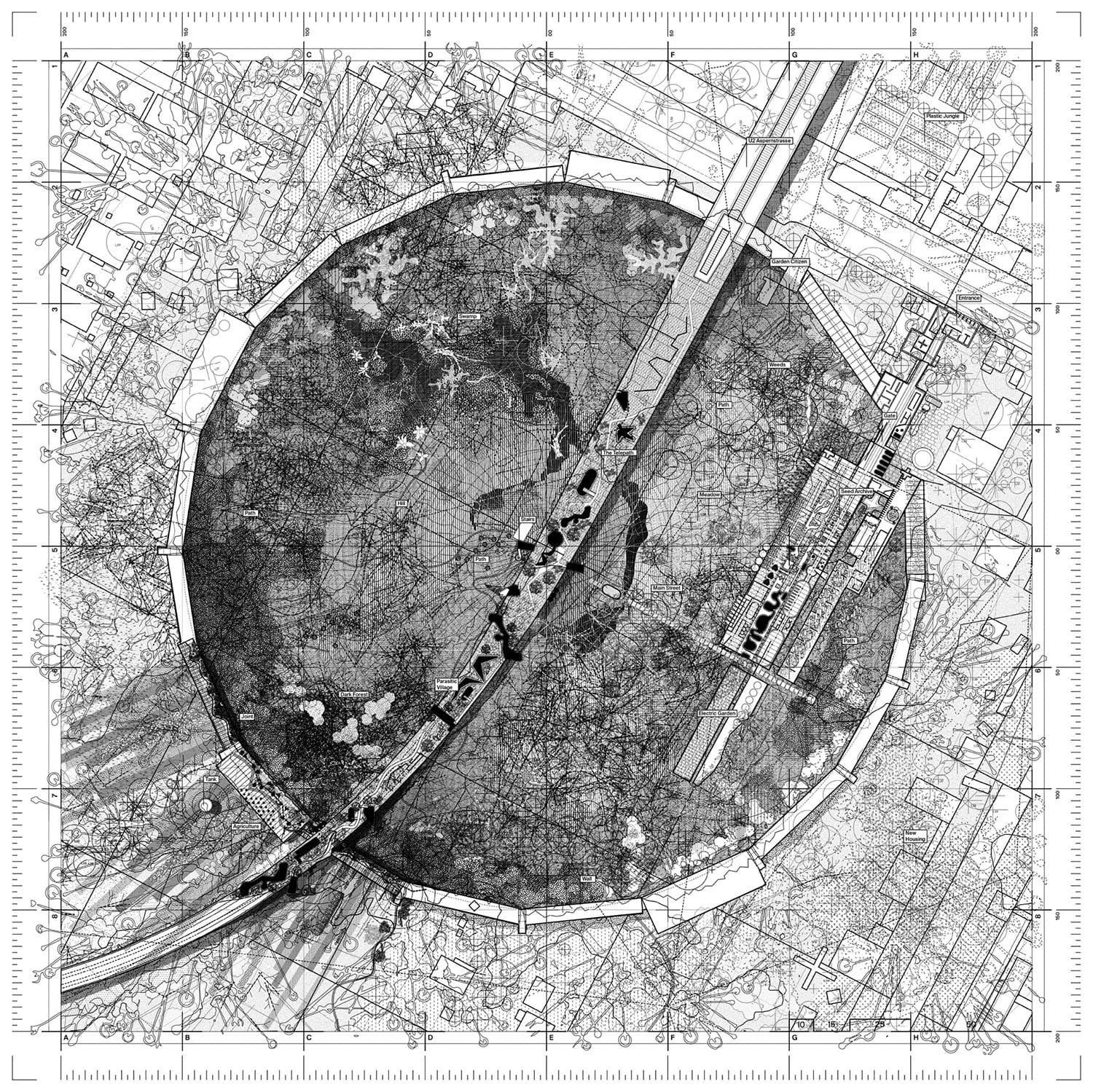

Die kreisförmige Grundstruktur dieses „Circular Garden“ ist eine direkte Referenz an die Form des Öltanks – wobei der Garten hier selbst das gespeicherte Medium darstellt. Während Öl eine Form von Energie ist, entstanden durch die über Jahrmillionen komprimierte und verdichtete biologische Substanz samt ihrer einst gespeicherten Sonnenenergie, bildet der Circular Garden das lebendige Gegenstück. Er stellt die Frage, welchem Zustand von Energie wir als städtische Gesellschaft die größere Bedeutung zuschreiben sollten. Der Kreis wird gebildet aus unzähligen Gewächshäusern, die bereits auf der Brache existierten, aber aufgrund mangelnder ökonomischer Bedeutung nicht mehr genutzt wurden. Diese werden abgebaut und in Form eines Kreises wieder errichtet. Sie bilden einen durchgängigen, umlaufenden Raum – eine Membran, eine Zellwand, eine Stadtmauer –, die den geschützten und verborgenen Garten im Inneren umschließt. Der weitgehend sich selbst überlassene und wild wuchernde Garten im Zentrum kann nur über einen Zugangssteg auf der Hochbahn der U2-Linie betreten werden. Der Besucher erreicht diesen seltsamen und fantastischen Ort einzig aus seiner Mitte heraus und scheint direkt darin verloren – doch er begreift mitunter auch die paradiesische Schönheit der ungebändigten Natur, mitten in der harschen Umwelt der wachsenden Stadt.

Part 1 — Site Investigation Lobau

Storage 1 — Natural:

„Remnants of the former floodplain landscape, such as wooded trenches from old Danube river beds, small ponds, and old forest fragments, hold a rich stock of different species of plants and animals. In the Au-forests there can be found up to 700 plant species, a quarter of the entire Austrian stock.“

Storage 2 — Artificial:

„The storage capacity of the entire area is 1.6 million cubic meters. […] That’s as much as 32 million tank fillings à 50 liters. Currently 4.75 million cars are registered in Austria. Strolling between the gigantic tanks, which are up to 30 meters high, quickly gives us an idea of how dependent the country is on oil. Six million tonnes flowed through the Lobau tank farm last year. Part of it is part of the iron reserve that will allow the country to spend 90 days without oil supplies.“

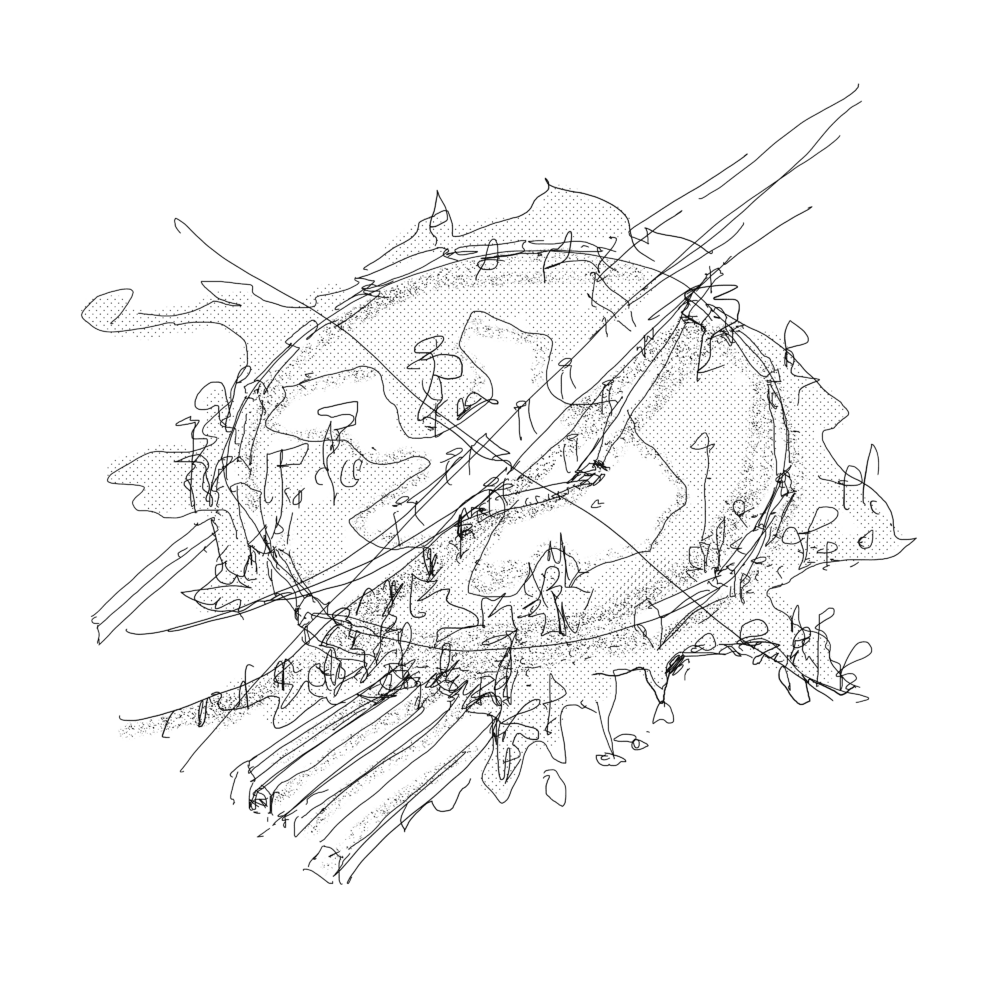

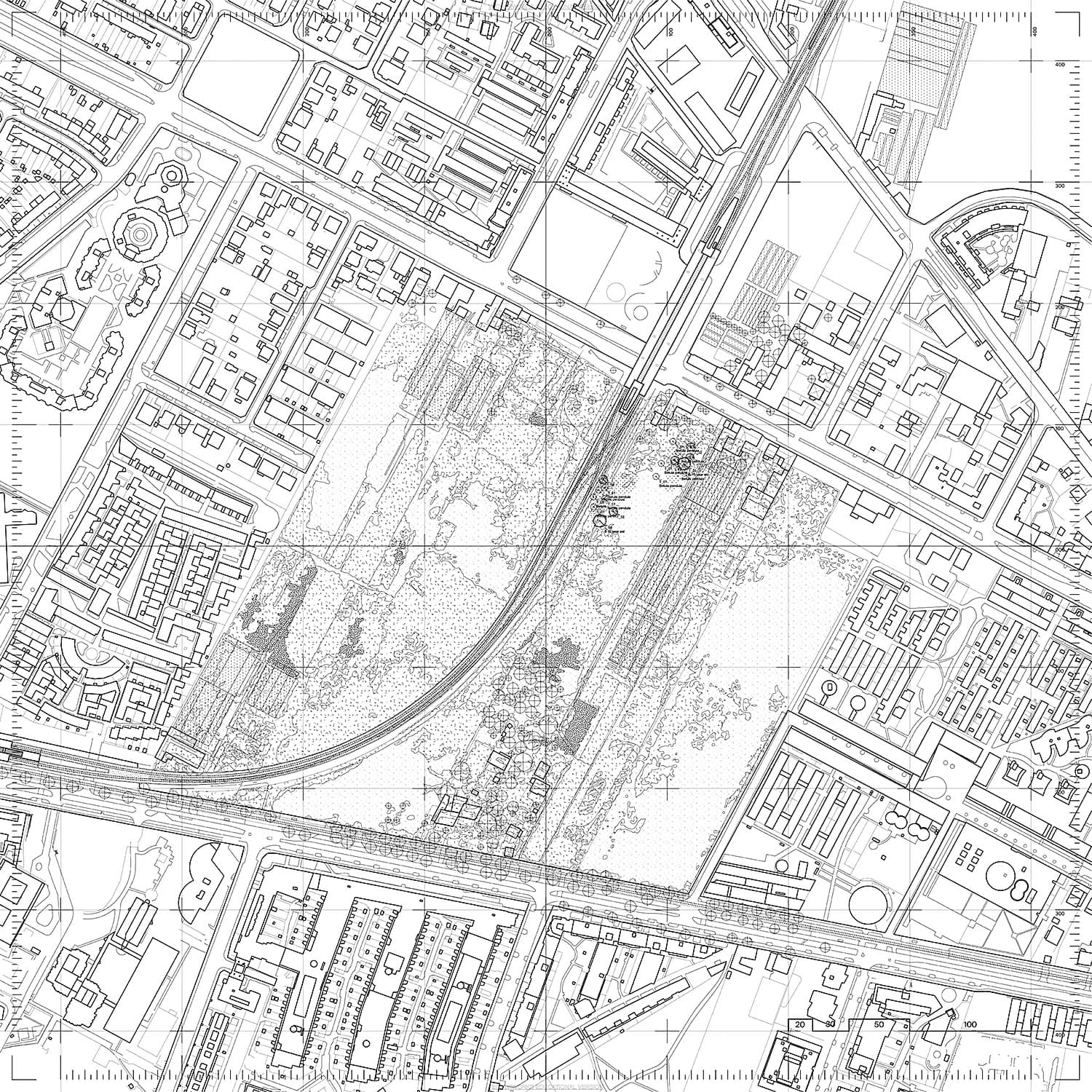

Part 2 — Projection Aspernstrasse

Part 3 — The Garden Manifest

The garden is an enclosed place, interior and exterior at the same time – intended to protect its inner goods: The plants and the soil, processes and information, animals and micro-organisms. The boundaries of the garden are physically present as a fence or wall but are also virtually defined by the boundaries of property, structure of vegetation patterns and spheres of influence. But the border is also an illusion: the garden‘s biosphere is inextricably linked to its surroundings and is influenced by every change in its parameters. Insects, birds, and mammals have their own range of motion that overcomes walls and fences, while the plants stretch their roots and branches in all directions and distribute their seeds with the wind into unsettled areas.

The garden questions the notion of inside and outside — we can enter it, hide in it but a the same time we are located ‚outside‘ of our built environment. If the garden is imagined as a room, we have to question what ‘material’ it is made of. Are the Plants and vegetation the structural skeleton of this ‘room’ or are they the actors and inhabitants? Are they the background scenery for anthropocentric narratives of are they creating their own complex stories.

The garden is also an emotional projection in times of imminent ecological collapse due to climate change and anthropogenic consumerism. It is an idealized symbol for a nature we have already forgotten a long time ago. The structure provides a protected container, for a variety of plant and animal species, and is the scenery for the play of natural cycles and a regeneration spot for local species.

The garden is labyrinth, meant to get lost in its overgrown structures. The human intruder enters in the centre and can explore paths to the outside, but never permeate the border. The threshold to enter it — take the elevated bridge along the U2-subway tracks — let only pass a view people at a time and make the garden to an intimate space. The circle as geometry creates the largest area with the smallest outer edge, it has a defined centre and is about to expand to the periphery in all directions. Former Greenhouse skeletons along the circles outline create the physical boundary of the garden — defining a oscillating existence of inside and outside.

The circular motif refers to the typology of the panorama. As a built structure, it can only be entered from the centre; the intruder’s gaze is drawn to the inside of its enclosure, producing an artificial horizon. The impressions of the respective viewer are projected onto the virtual screen of the translucent glass panels as subjective imaginations of nature.

The circle is a cell with a nucleus for information storage (Seed archive), a membrane for protection and metabolism (The Wall), and a multitude of organisms that drive the growth and decay processes inside (Vegetation Patterns, Parasitic Village). The cell wants to divide itself to expand and connect with others, reactivate an exhausted urban landscape, create a healthy soil and let grow a feral forest city in the future.

The circle refers to the oil tank (Lobau), which derives its characteristic cylindrical shape from the structural need to contain a liquid material. The cylinder as a basic geometry, as a circle extruded in the third dimension, also marks a psychic container that protects stored ideas and information from the environment. As a Funktionskreis des Lebendigen the circle defines an experimental area, a stage for natural processes to play. Its lack of program is also its intention: To let happen what creates itself if nothing is done (Wildwuchs on a fallow).

Part 4 — The Circular Garden

Garden Plans

Garden Sections